Portrait of Luca Pacioli, Jacopo de' Barbari, 1495

Foreword

Mr. Martino’s Ledger is a whimsical story about a Renaissance Italian merchant and his daily life of commerce in the heart of Sansepolcro, a small hamlet in Tuscany. The inspiration for Mr. Martino’s Ledger came from Luca Paciolio’s renowned work, Summa de Arithmetica, a textbook about geometry, trigonometry and most famously, double-entry accounting. Paciolio was the definition of a “Renaissance man” and in addition to being a Fransciscan friar, mathematician and chess player, he also collaborated with Leonardo da Vinci on De Divina Proportione, another math textbook. Pacioli’s contribution to modern accounting is undisputed, and his examples in the Summa leave a lasting legacy.

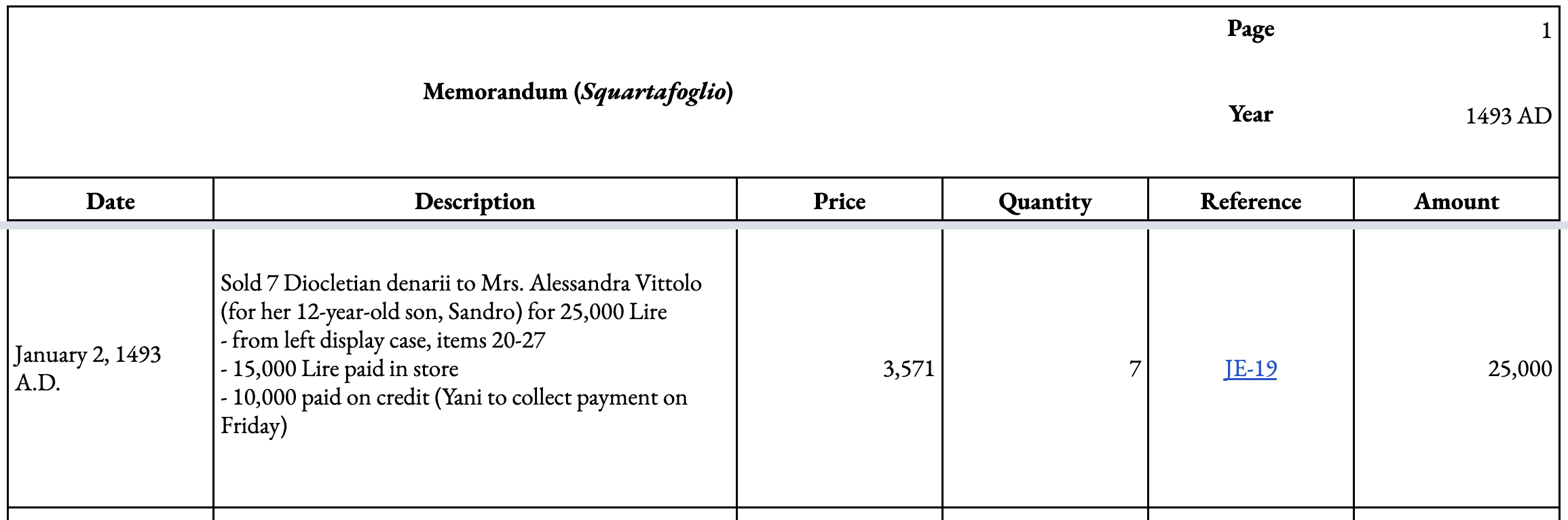

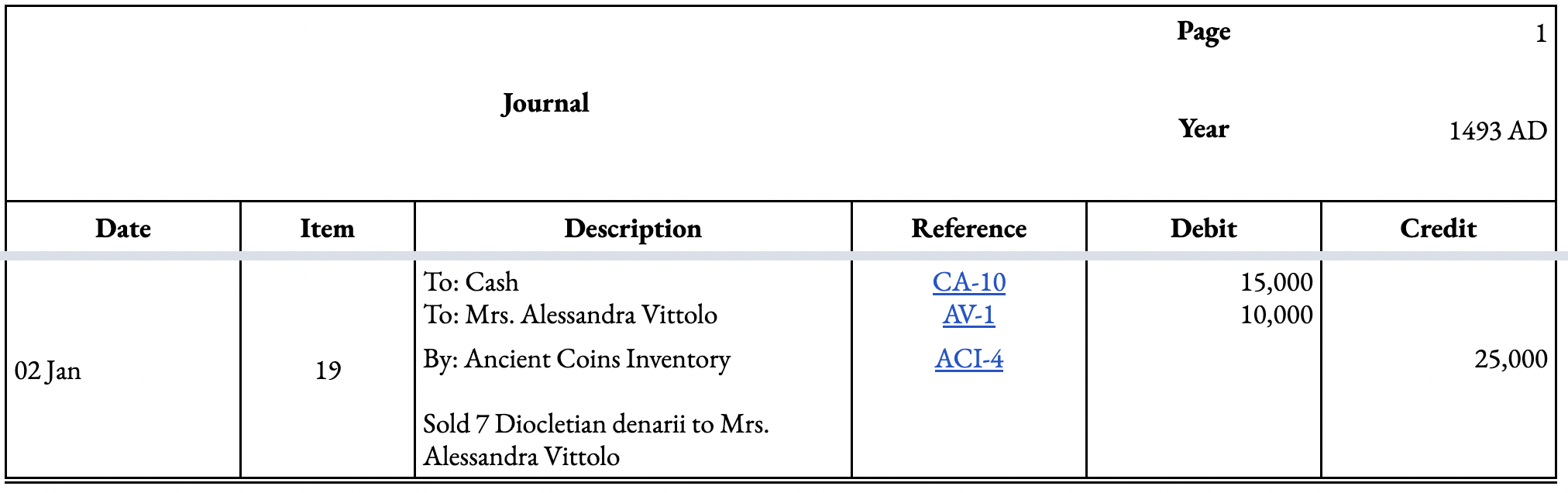

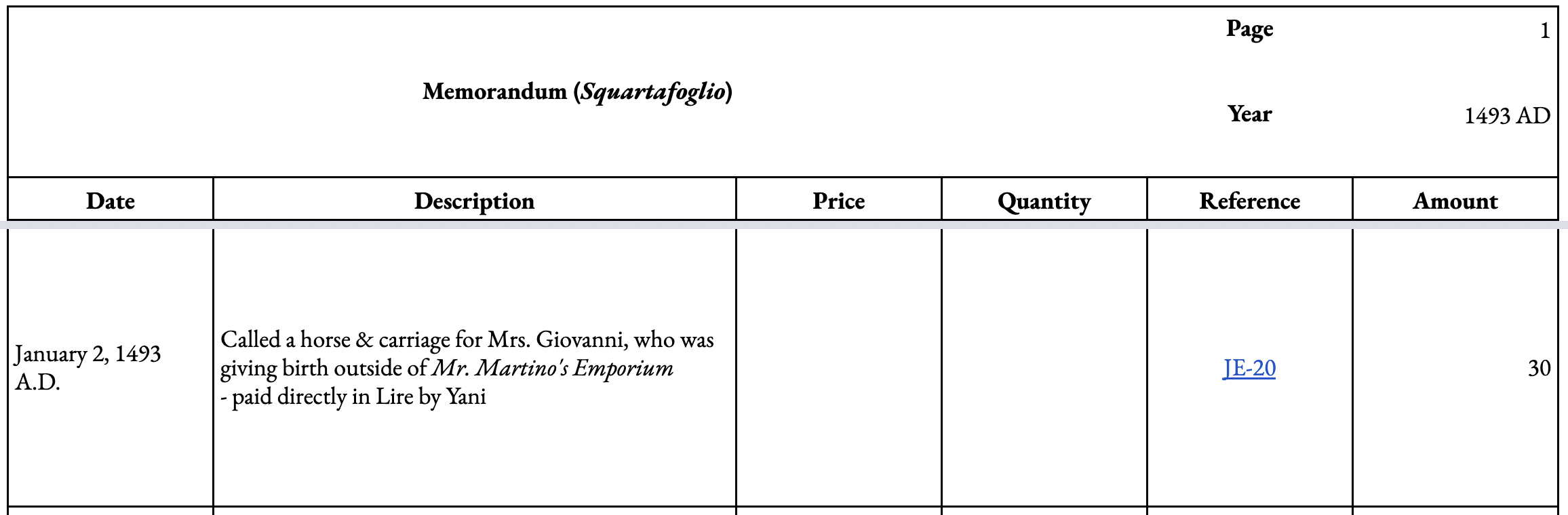

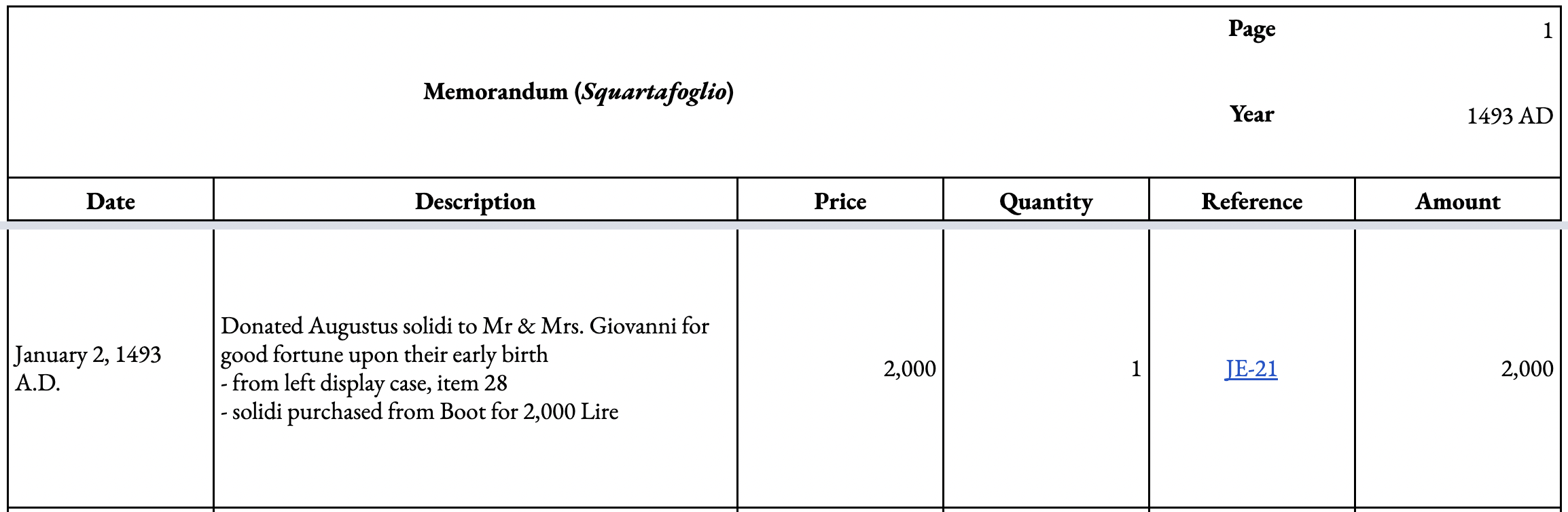

While Mr. Martino’s Ledger is a short story, it’s also the case study for a detailed accounting system in the style of Pacioli. Transactions described in the text, such as selling inventory or paying for a carriage ride, have corresponding memorandum, journal and ledger entries in a separate spreadsheet. The motivation for writing Mr. Martino’s Ledger was so that I could create an accounting system using the knowledge gained from reading Summa de Arithmetica.

The spreadsheet is divided into six tabs:

-

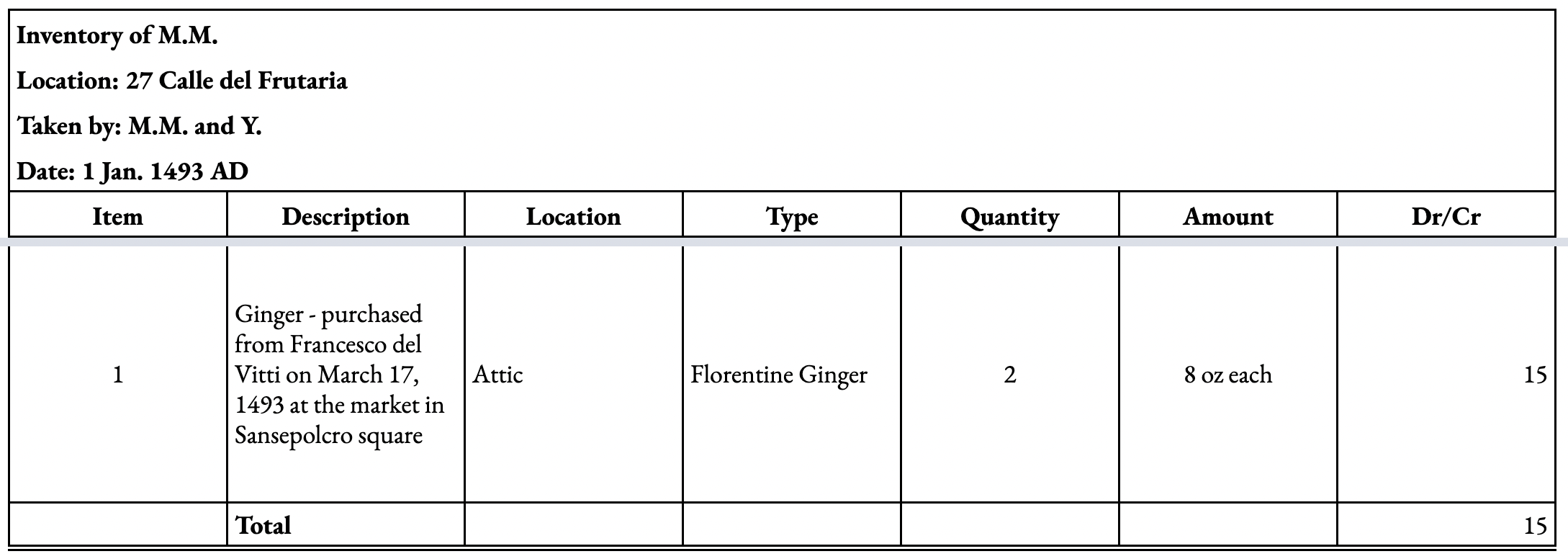

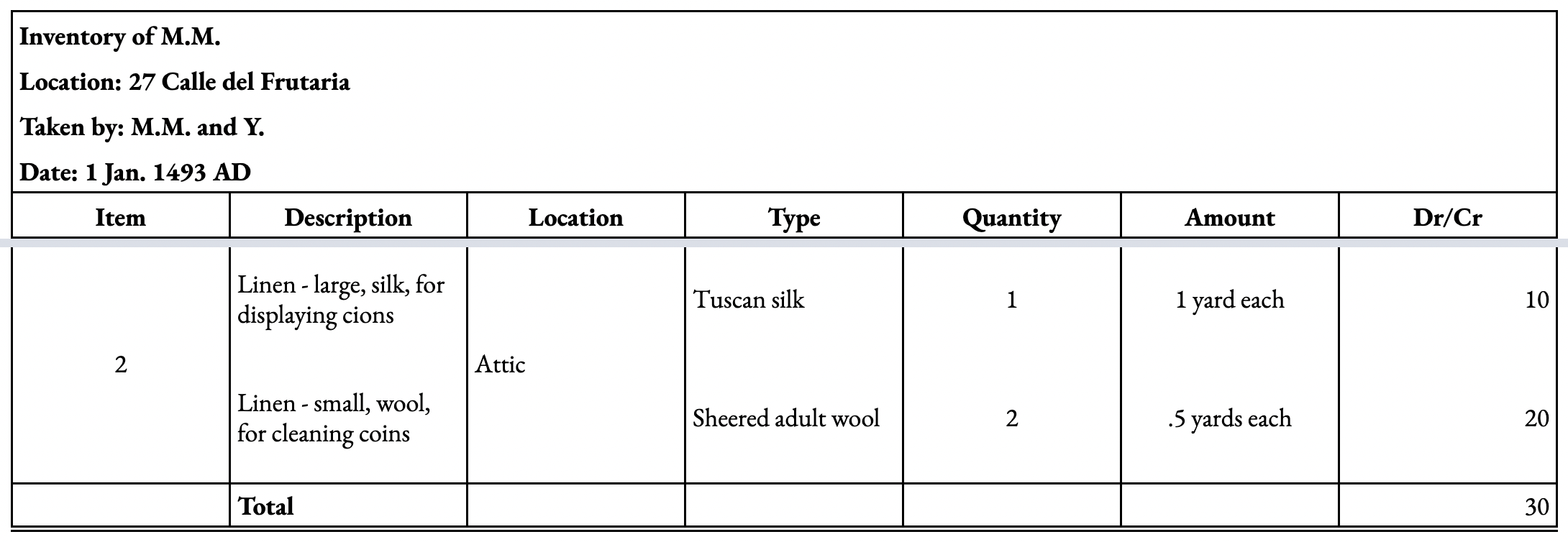

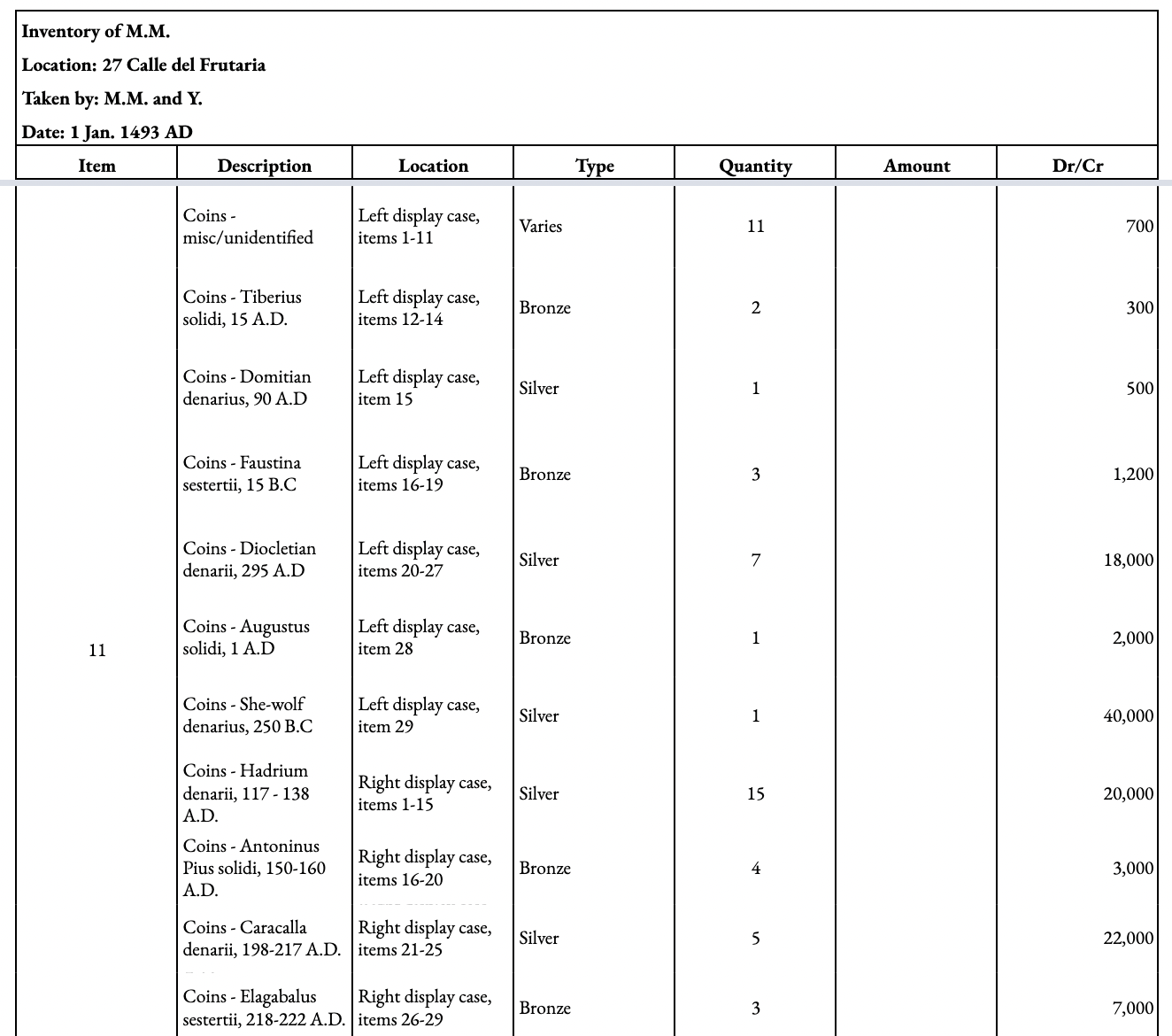

Inventory - a listing of all the inventory denoted in the opening section of the story

-

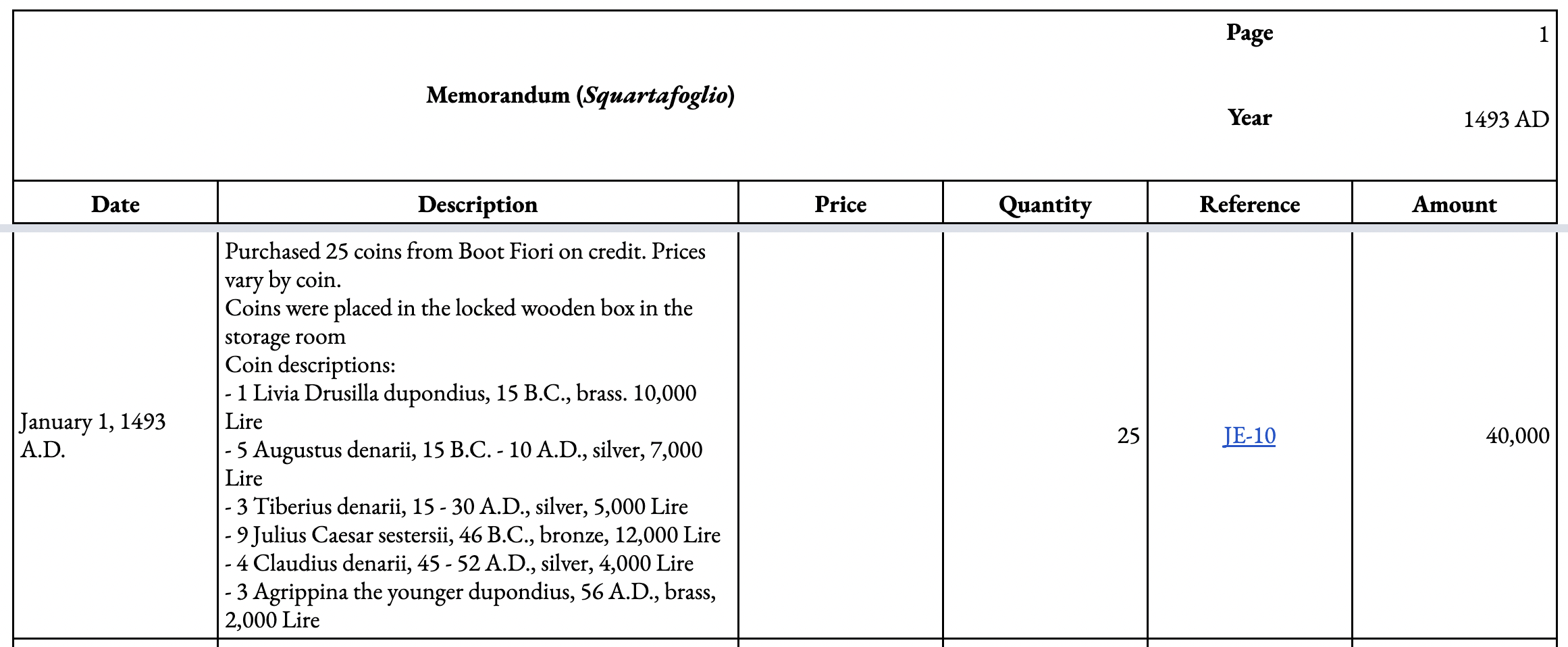

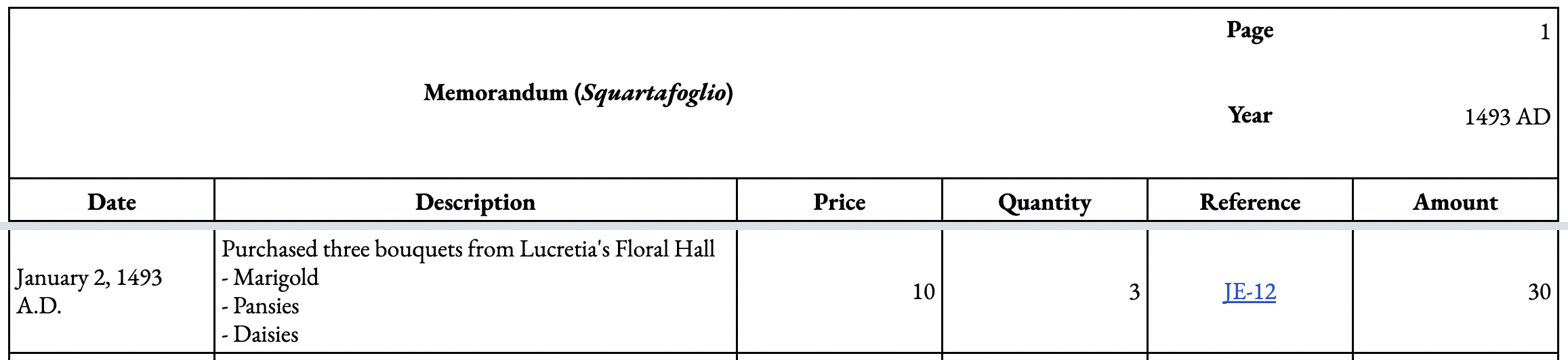

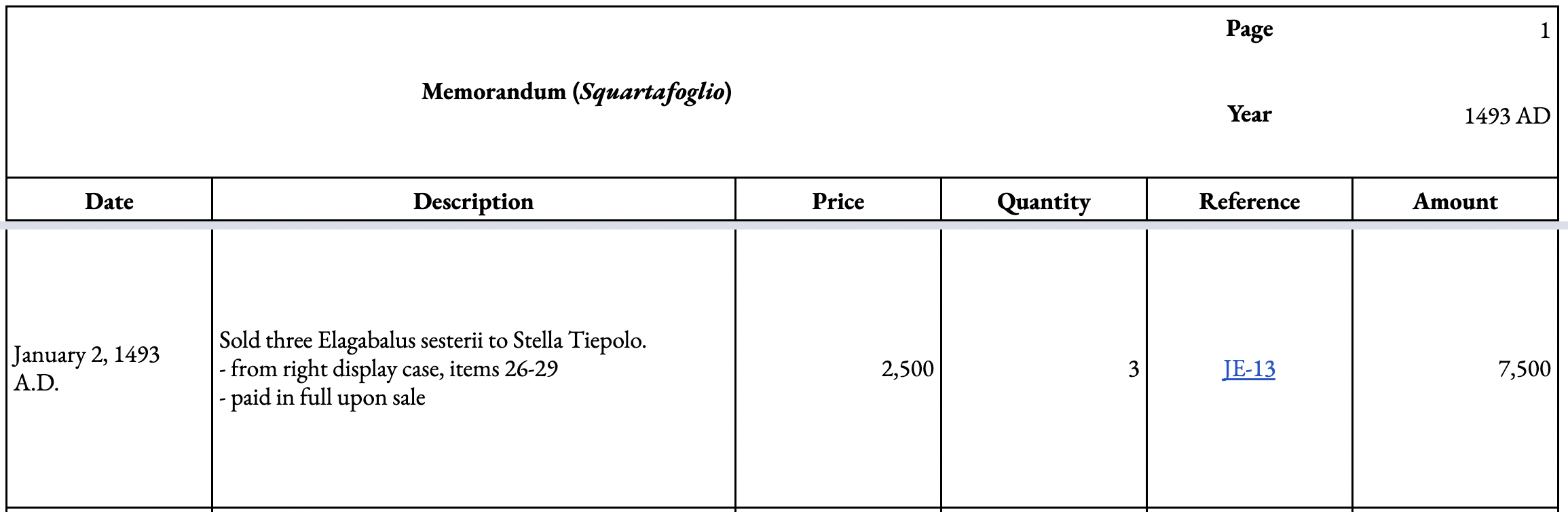

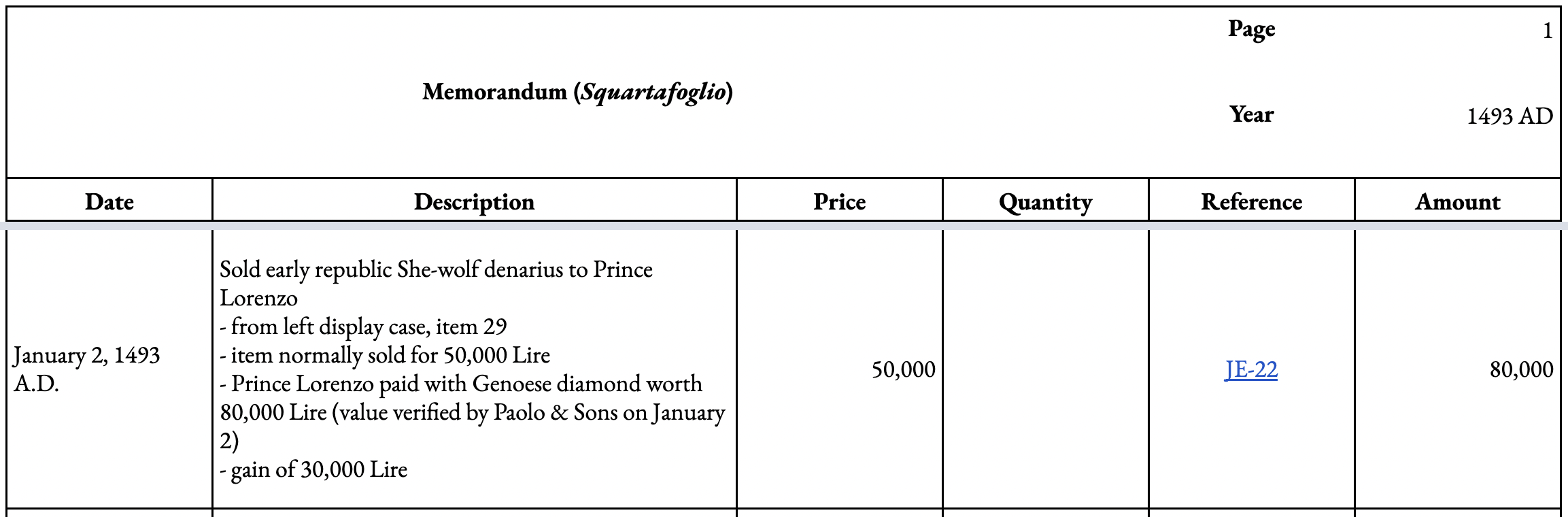

Memorandum (Squartafoglio in Italian) - a day book whose purpose was to “record all business transactions, regardless of size, in chronological order”

-

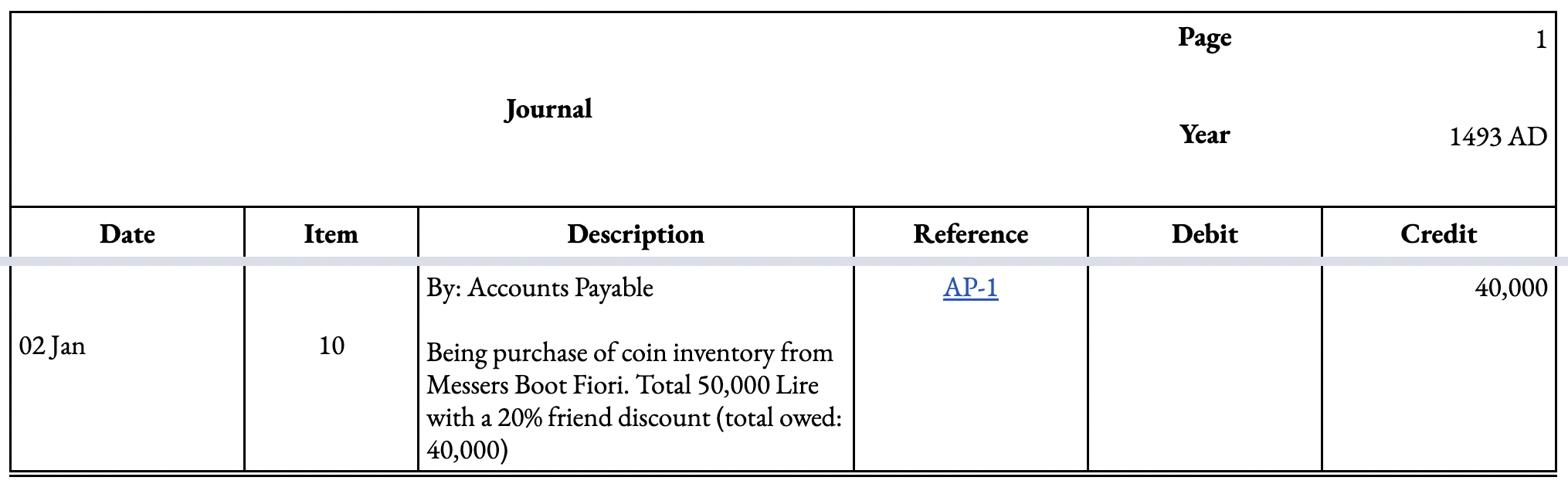

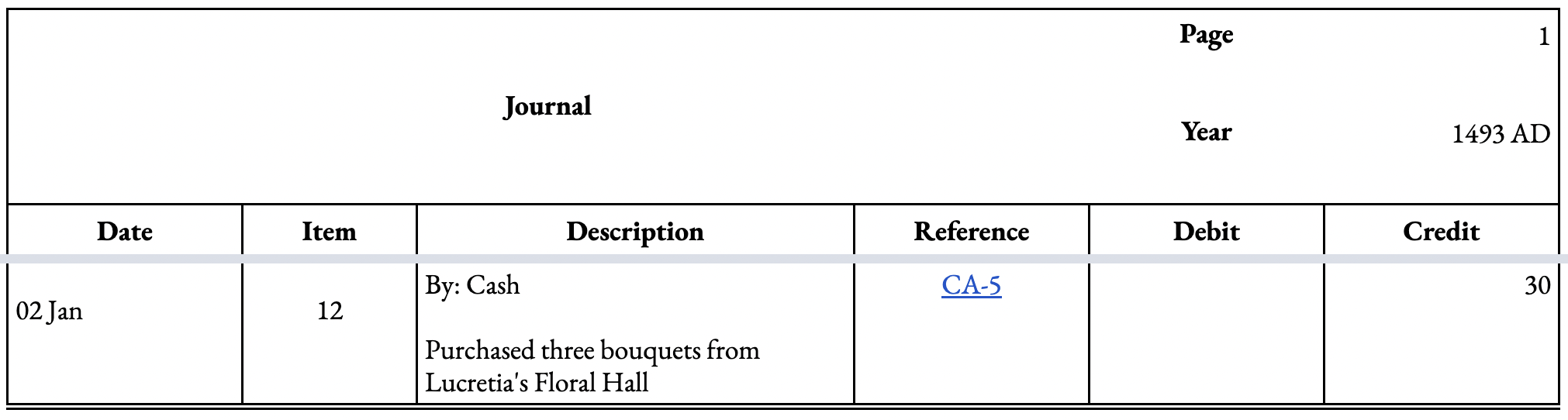

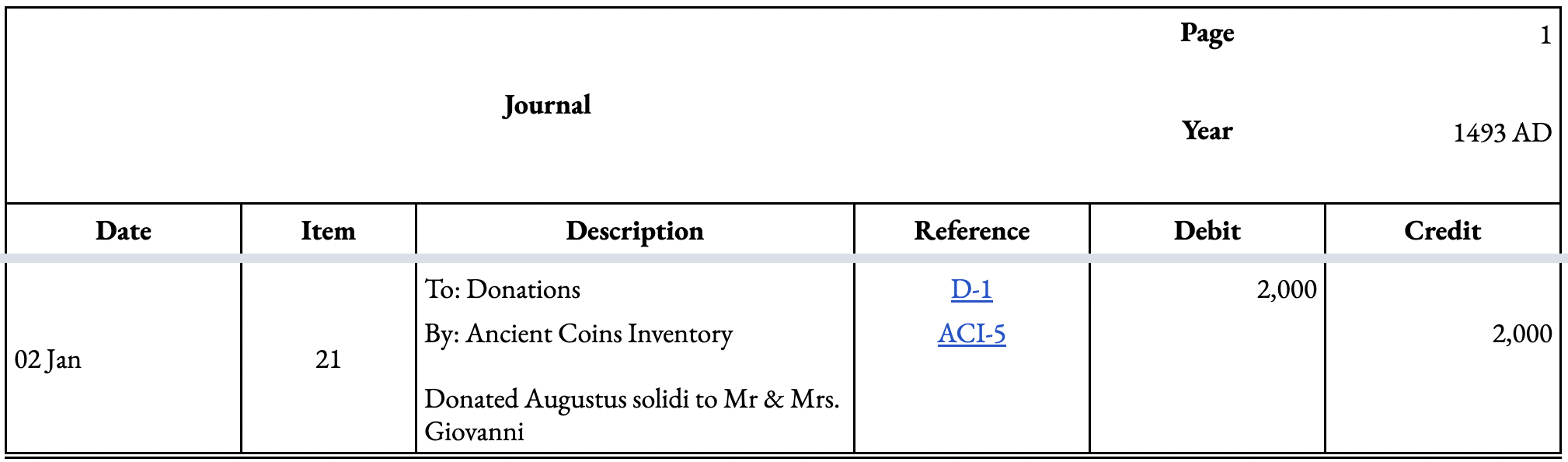

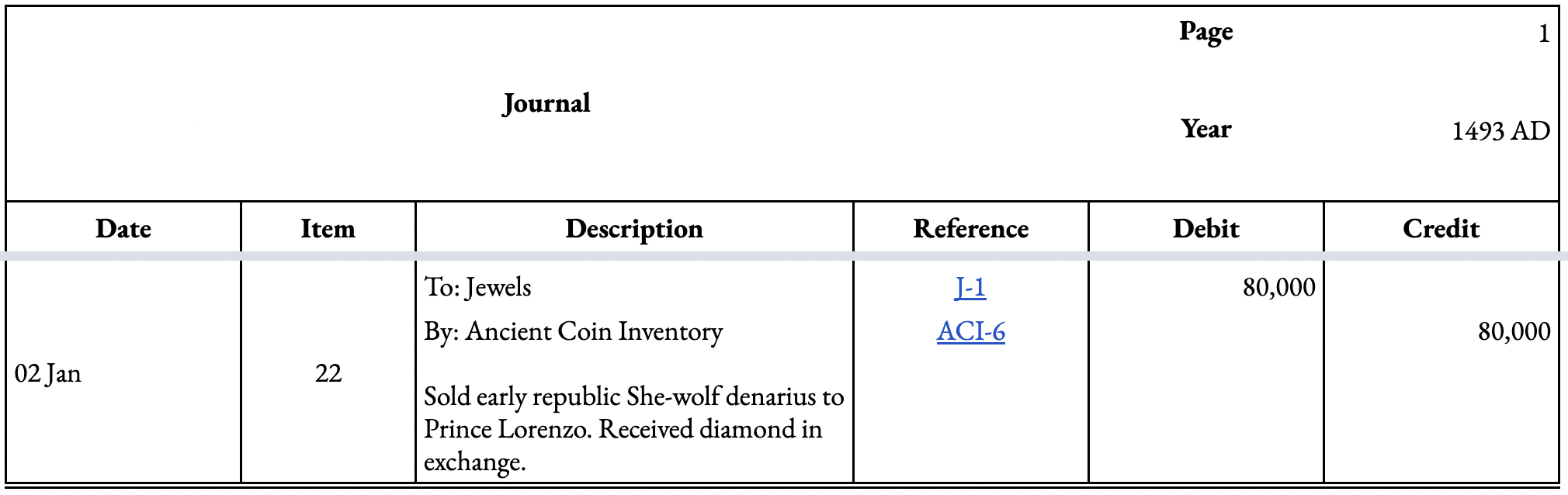

Journal - transactions from the memorandum are converted into journal entries (debit and credit or to and by in the Renaissance) and logged in the journal

-

Ledger - the third book of accounts that lists all accounts and entries booked to them

-

Trial Balance - an extract of all ledger accounts and their ending debit or credit balances (all debits and credits across all accounts must equal)

-

Disclosures - a listing of relevant footnotes about the accounting techniques used in the Summa

Note: all of the entries are denominated in Lira (plural Lire), a currency that was common during the 15th century and used until the late 1800s in Italy.

Hopefully this story piques the reader’s curiosity about the origins of double-entry accounting and its impact on modern capitalism today. It’s evident that accounting hasn’t substantially changed form in over 500 years, which is a testament to the flexibility of debits and credits.

One of my favorite quotes from the Summa reads, “The very day a debit is born, it has a twin credit. So it is quite natural for them to always go together in your books.”

I hope you enjoy this unusual tale and gain as deep an appreciation for accounting and Italian history as I have.

Ciao.

Glossary with key terms provided at the end of this story. Spreadsheet with full accounting system can be viewed here.

Mr. Martino’s Ledger

Mr. Martino groaned as he lumbered up the small wooden ladder that led into his rat-infested attic.

“Ahh, let’s see what treasures are hiding in the attic this week,” he wheezed, waving a few rats away with a twitch of his fingers.

It was inventory day for Mr. Martino, which meant scouring his tiny shop for all the assets he owned and tallying them in his leather-bound inventory book. It was his least favorite day of the year since it meant hours of putrid dust, watering eyes and a hunched back as he poured over what little things he had in this world.

“Yani, are you ready?” asked Mr. Martino, turning to his assistant.

Yani was the courier boy and apprentice to Mr. Martino’s shop. He fled from the Dardanelles of the Ottoman Empire when he was eight years old and washed up in Venice on a shipping vessel. His family was persecuted for being Christian, and it was rumored that his sister and mother died while trying to escape. Yani never spoke a word about them. He was tight-lipped and dark-eyed, although he was known to crack a smile whenever Mr. Martino told one of his “infamous” jokes.

“Yessir,” said Yani, opening the inventory book and fishing around his pocket for a quill. “But this time, make sure no rat droppings fall on my head. I just washed my hair.”

Mr. Martino laughed and patted Yani’s head like a loving pet owner does to his riled up mutt. His hair was sticky with olive oil and essence of juniper, which meant Yani had a date with one of the local wenches later that night.

“Two eight ounce jars of ginger purchased from Francesco del Vitti on March 17, 1493 at the market in Sansepolcro square. I remember a great deal of haggling and a punch or two before we settled on a price. 15 Lire total,” barked Mr. Martino. Yani dipped his quill in pig's blood ink and started scribbling furiously.

“One large silk linen for displaying coins. Handmade by Ms. Lippa Lottini and purchased for 10 Lire. Two smaller wool linens bought at Guipi’s general store for 20 Lire and used for cleaning mold and other parasites off the coins.”

They crawled their way around the attic (carefully avoiding the rats who were busy nibbling on bits of moldy ginger) and recorded everything, down to the last napkin ring Mr. Martino bought from a circus ringleader in Sardinia in 1450. Their faces were blanched with perspiration but a certain gleam had entered both of their eyes. Mr. Martino and Yani, although thirty years apart in age, shared a love for counting and for making sure every asset was in its proper place.

“The attic has been cleared!” hooted Mr. Martino, taking a mammoth swig from his flask of mulled wine and throwing the bottle over to Yani. “Drink up, my boy, we’re going to need all the zest we can get for the coin inventory.”

Mr. Martino locked the storage room door behind him and walked with Yani into the heart of his Ancient Roman coin collector’s store. There was velvet everywhere, from the drapes lining the frosty windows to the linens in the display cases to the portly suit hanging by the front door. The room was lit by a choir of candles placed precariously between two long cases. Everywhere was flashing with the glint of coins, all harvested from the bowels of Ancient Rome. Hadrian glared from the top left shelf, Trajan was smirking by the window and Nero was galumphing by the checkout register. History was breathing from all of the dusty, luxurious corners and Mr. Martino stopped to inhale it all.

He thought about the glory of the Forum and all the late nights he spent excavating old temples. The hairs on his neck stood up.

“Alright Yani, it’s Tuesday night, which means we have to be finished with the main inventory by 9:15 p.m. so I can have my nightcap with Boot. Let’s see if we can set an inventory record.” Mr. Martino and Yani exchanged mischievous smiles and they darted off, moving almost like whirling dervishes as they picked up and examined all the coins in inventory and recorded them.

“Two Tiberius solidi from 15 A.D., slightly tarnished but otherwise recognizable. Bronze.”

“One Domitian denarius with a slight dent in the foreground. Silver.”

“Three Faustina sestertii from 15 B.C., in need of a good cleaning. Bronze.”

“Two Diocletian Antoninianus’, in excellent condition despite the debasement of silver in 270 A.D.”

The men became drunk with the help of the mulled wine and intoxicating relics. Yani’s hands were a purplish black from all the pigs blood that had dried up. His hair, however, was still perfectly oiled and smelled like the Uffizi gardens. Mr. Martino pulled out his latest bank statement from the Bank of Medici and recorded the cash sitting in his account. 100,027 Lire, the statement read, and Mr. Martino beamed, feeling like Cosimo de’ Medici himself.

Two hours later, the inventory was finished and the leather-bound book was closed shut. It would be reviewed by Mr. Martino again in the morning (to check for inaccuracies, of course) but the evening was late and both of their hands were cramped and smelling of odious metals. Yani stood in front of an old, cracked mirror and smoothed his hair down over his rather protruding ears.

“Going out with Mellia again tonight?” inquired Mr. Martino, looking wistfully at Yani’s full head of hair and wrinkle-free forehead. Youth eluded him like a happy relationship and his head was temporarily amused by visions of dresses and full lips and wine.

“Yessir, she’s expecting me to pick her up at 9 and then we’re going to The Sullied Goat for some stew and mead.” Yani smiled devilishly. “And then I’ll see if she wants to take a walk by the river after dinner.”

“Say hello to Alessandra for me,” said Mr. Martino in an off-hand way, pretending not to care that Yani would be within a hair’s breadth of the (married) woman he loved.

“Sure, but she’ll probably be busy cleaning up all the sop from the drunk men. The Sullied Goat is a fine inn, but they’ve got to start kicking those raging drunkards out.” Yani sounded too wise for his sixteen years of age, and Mr. Martino chuckled.

“Alright well I’ll see you tomorrow then - be here half past dawn so we can polish the new coins I’m getting from Boot tonight.”

Yani saluted like a pompous cavalryman and left Mr. Martino’s Emporium, the soft bronze bells jingling on his way out.

Mr. Martino suddenly heard blows and sharp kicks on the back door of Mr. Martino’s Emporium. The lock, an iron beauty recently installed by a Mr. Alighieri, was being violently jangled up and down on the wooden door. Then a quiet click pierced the silence as Mr. Martino stood quivering in his slippers.

The door was blasted open and a worn brown hat came into view. Boot appeared, his charcoal eyes glaring and the scar across his temple deep and unforgiving. An ax clipped him when he was moonlighting as an excavator at the Roman forum back in the 1420s, and he wore the scar proudly, ominously.

“Boot!” exclaimed Mr. Martino, “why couldn’t you just use the front door? I’m absolutely drenched in sweat right now.” Mr. Martino was suffering from a bout of nerves and this recent intrusion did not help.

“That wouldn’t make quite the same entrance, would it?” drawled Boot in his accent, a mix of rough Sicilian and island Greek. “Plus, I couldn’t be late for our meeting and I was coming down the back alley anyway.”

Boot, in addition to being Mr. Martino’s ancient coin dealer, was Martino’s only real friend. The two skulked amongst Roman ruins in their twenties and shared everything, from their coins to their bar women. Mr. Martino unscrewed the cap on his flask and gave it to Boot, who drank deeply from the spout.

“Ah, that’s better. I’ve had a terrible day of it,” sighed Boot, sitting on the chair behind the register and taking a 10 Lire note out from it. “Mind if I take this? You can draw down the debt you owe me.”

“Pinched for cash? Don’t try to overprice your coins if you are - I can smell a perfidious price from 10 streets away.”

Boot grinned and stuffed the ten-note into his breast-pocket.

“Reni was singing the chorus from Antigone tonight, and I wanted to give him a little something.”

Reni was the local beggar of Sansepolcro who sang doleful Greek tragedies on the corner of Dittalini and Riggolo streets. One-legged but full of blood, Reni’s voice haunted the small town until all the inhabitants were lulled to sleep by the ghost of Oedipus.

“So what have you got for me? Any Trajan silvers?” asked Mr. Martino hopefully, trying to get a glimpse of the coins Boot was pulling out of his pocket. The men could chatter about ancient money for hours, the round amulets and their inner mystery bringing them back to their twenties. The romance of it all still stunned them now, even though that was long since gone and their bones ached and teeth chattered at night.

“Sfortunatamente no. There wasn’t a Trajan in sight but I labored to find these jewels.” Boot fanned a litter of coins across the desk like a magician and waved his hand. Mr. Martino peered at the disks intently, discerning the faces of Patrician men long since dead. There was Augustus, with his strong nose and boyish haircut. Caligula with a faint beard and delicate laurel wreath around his psychotic head. And Septimius Severus, with his uncontrollable curls and pharaonic eyes. Mr. Martino stooped lower to take in the scent.

“I smell decaying earth…with notes of poppy and musk. Where did you get all of these?”

“In our usual spot, with a few detours to the Circo Massimo and Pompey’s Theater. The ruins look the same as when we first discovered them, not a stone overturned or touched.”

Boot sighed and started counting invisible digits on his fingers.

“The whole lot is 80,000 Lire, which includes an “old friend” discount of twenty percent mind you. What do you say?”

Mr. Martino jerked his head back to reality. He was far away, back in his youth discovering the rush of exploration and adventure for the first time.

“Remember when we first ran into each other?”

Boot dropped his hands and grinned, a glazed look indicating he’d been sucked into the time machine as well.

“Yeah, we were both sneaking around Trajan’s Market, right by Trajan’s Column, in the dead of night. I don’t know what the hell we were both thinking, but I do remember how bright the Column looked that night. Those reliefs - the beasts in stone - seemed to be dancing. I was looking for a sestertii with Pompeia Plotina on it, a rare gem.”

“And I was half-drunk fishing around for a small bust of Trajan,” laughed Mr. Martino. “I thought you were going to kill me! Or worse, that you were a ghost! A rather smelly ghost.”

“I was in a haze back then, digging for over twelve hours a day looking for a coin or piece of marble that would make me famous. Now I dig for five hours and my knees get stiff.” Boot sighed and returned to examining his loot. “So what do you say? 80,000?”

“I’ll do 50,000 Lire for all coins from the Julio-Claudian era - actually 40,000 with the discount.”

“Give me the rest of that mead and we have a deal.” Boot started drawing up a breakdown of all the coins purchased, including their year, weight, selling price and namesake. He made an additional copy for Mr. Martino so he would have documents to present to the tax authorities come audit time.

Boot made the sign of the cross every time he entered a new coin and murmured “Deus sit hac pecunia” (Let God be with this money).

“I’ll tell the bank to send you the money tomorrow,” said Mr. Martino. The two men spit on their palms and shook hands, their lips red with mead.

One flask. Two flasks. Three flasks, four. Middle evening slipped into midnight as the men sat and reminisced on the floor of Mr. Martino’s Emporium. A trail of ants was leading from the right display case into the storage closet, no doubt to greet their compatriots in the attic.

“Same time next week?” slurred Boot as he got up to leave.

“Wouldn’t miss it for anything,” winked Mr. Martino as he saw Boot out - through the front door.

A blinding light poured through the crack in the velvet curtains. Mr. Martino slowly opened his eyes and found himself lying prostrate on the floor, his bottom in the air and his eyes a few inches from the benign face of Marcus Aurelius.

“My dear Marcus, please give me some stoic wisdom to get through today.” Martino sighed and rubbed the goop out of his eyes. His clothes were sputtering dust bunnies and his teeth were coated in a sugary veil. It was definitely time for his biweekly bath. Martino checked his pocket watch and saw it was 6:30 in the morning, which left plenty of time to wash up, grab a bite at the inn and get back for the Emporium’s opening at 7:30.

Locking the front door, he suddenly noticed small arms and spaghetti thin legs wrapped around his feet. They were bouncing up and down and shouting things like “Buongiorno Mr. Martino!” and “Looks like someone needs a bath!”

The pile of limbs belonged to Lucretia, the florist who owned the storefront next to Mr. Martino. She was a lively woman who always smelled of wheat and tobacco and had five children running around her at all times.

“Alright children, time to get back to your blossoms. Buongiorno Lucretia!”

Lucretia looked harried as she swept the cobblestone in front of her store and wiped a strand of hair out of her tired eyes.

“Aye, hello there Mr. Martino. Sorry about the kids, but they’ve full of pent up energy. Must be all the rice pudding I fed them for breakfast.”

“No worries at all. Say, you got any flowers I can buy? I’m looking to spruce up my shop. I’ve just bought some marvelous new coins that are going on display today.”

Mr. Martino bought a few bouquets of marigolds and pansies for 30 Lire and set off for the public Arezzo bathhouse.

An hour later, he waltzed back up to the Emporium to find Yani waiting by the door, his hands in his coat pocket.

“How was your date with Mellia?” asked Mr. Martino.

Yani sighed. “I don’t wanna talk about it. She didn’t want to go on the riverside walk with me because of something about me and her being from different classes. I mean, she’s just an apprentice too!”

He kicked the side of the building in exasperation.

“I don’t understand Sansepolcro sometimes, it wasn’t like this back home.”

“Well luckily I procured 25 coins last night, so you can focus your energy on polishing them up!” said Martino cheerfully, just happy he didn’t smell like dog's breath anymore. “Besides,” he put a hand on Yani’s shoulder, “Women are fickle, she’ll come to you when she’s ready.”

The first customer meandered in at exactly 8:10 a.m. It was Stella, the oldest woman in Sansepolcro who used to be an opera singer for the court in Venice. Her teeth were rotting, her hair was matted and she could barely walk, but there was still a youthful air about her, even if it was shrouded in sadness.

“Buongiorno Stella!” boomed Mr. Martino, looking up from his display case to peer at the tiny old woman. “How can I help you?”

Stella peered at him, one eye a watery blue and the other a frozen cataract.

“Oh, you know how it is being nearly eighty - can’t remember anything to save my life. Not that I have much time to live anyway.”

Her silver silk dress swished behind her and made a noise like a broomstick sweeping the floor of a stable. She was famous for droning on about her court performances for the Doge back in the early 1400s, like anyone cared. But Martino gladly indulged her, happy to be in the company of someone older than him.

“Is there any particular coin you’d like to look at today? What’s the occasion, if I may ask?”

Stella rapped on the glass with her gnarled hands, her knuckles veined and twisted sideways near the top.

“Well you see, it’s about a man. Always is. We met one ‘eve as I was singing in the choir and he approached me after. All shy and looking at the floor like. I asked him for supper and he said yes.”

“And how old is this lucky fellow?”

“God only knows! But he doesn’t look a day ‘bove four and ten. Which is why I need something to impress him with.”

“Well in that case, I highly recommend our collection of Elagabalus sestertii. He was the most effervescent emperor who hosted parties with roses falling from the ceiling. Quite a picture if you can imagine being there.”

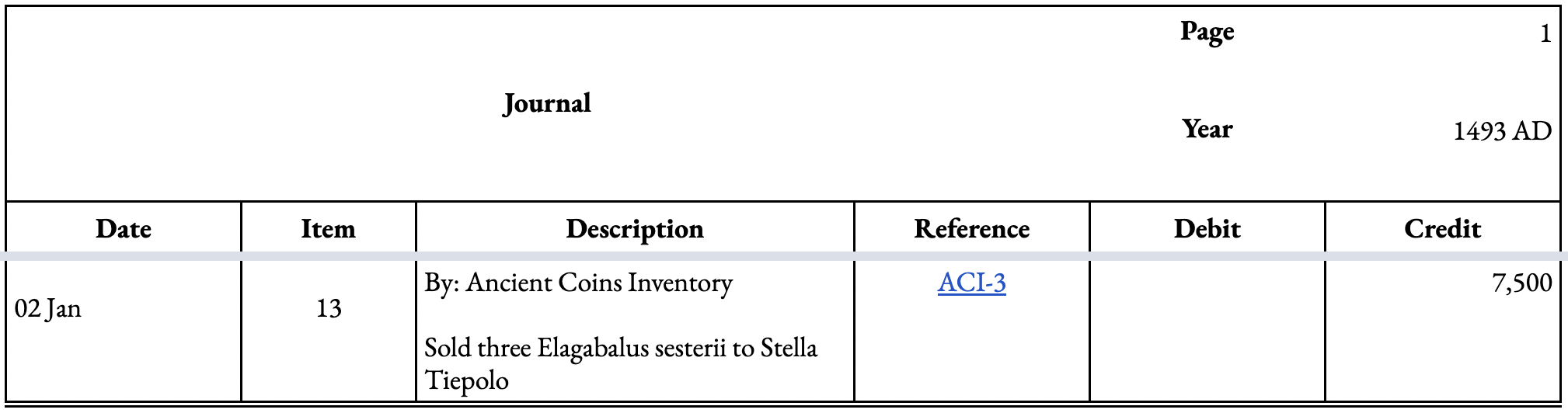

Mr. Martino, being the impeccable salesman he was, sold three Elagabalus coins to Stella for a total of 7,500 Lire. He wrapped them in silk and placed them in a drawstring bag he purchased from the leather maker this morning. While he wrapped, Stella was serenading him with tales of Tommaso Mocenigo and Francesco Foscari, two Doges that she sang for. Apparently modesty went out the window where the Doge was concerned and Stella had no qualms about that.

“Stella, how does it feel to be the oldest person alive in Sansepolcro?” asked Mr. Martino, half afraid to hear the answer from this frail shadow.

“Like no one in the whole world remembers who you are,” said Stella.

Miraculously, there was a wide, toothless smile on her face. She dropped the Lire into Martino’s hand and wafted through the door like an age-old smoke.

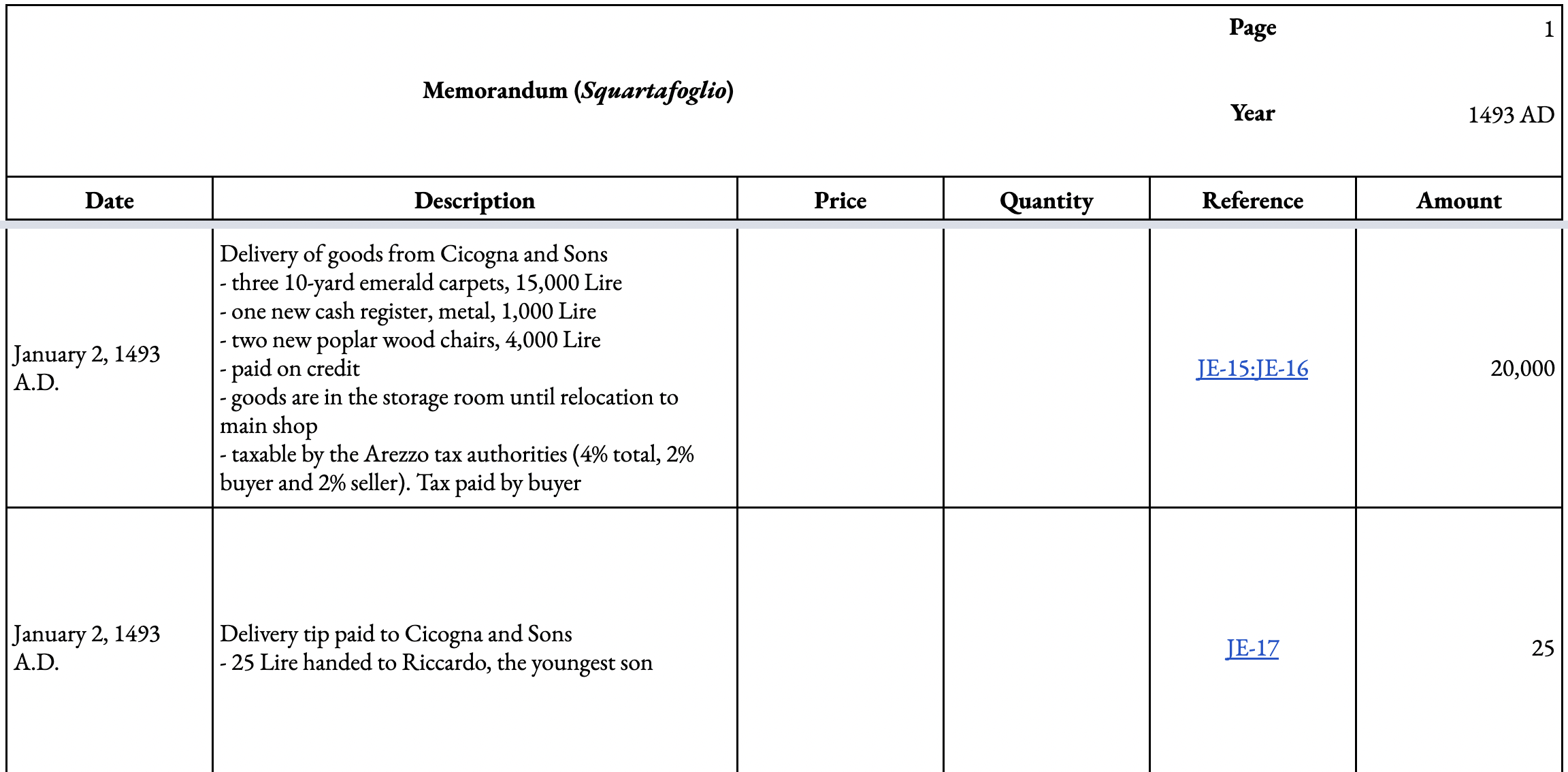

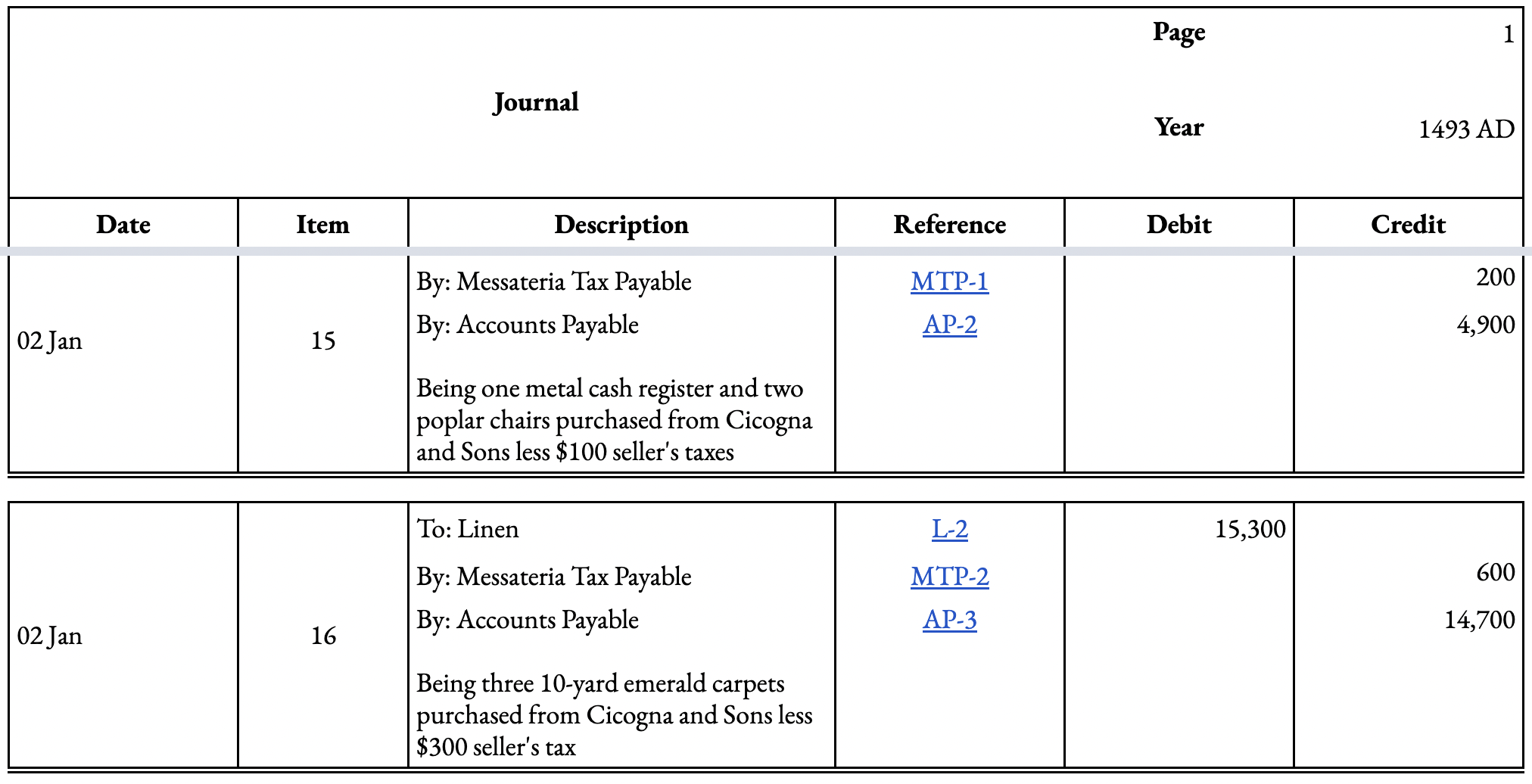

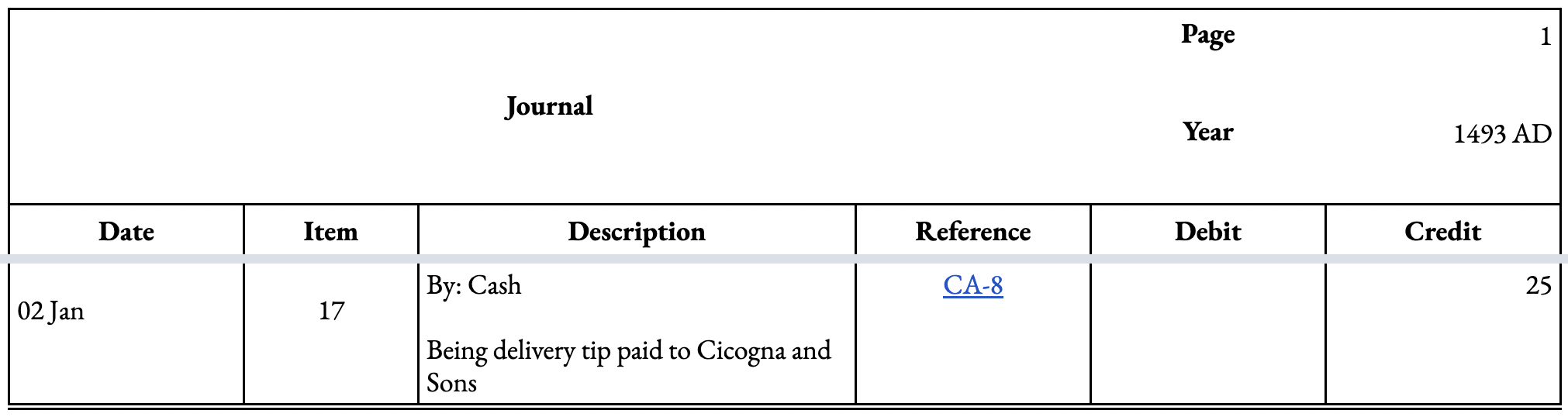

Martino didn’t have a second to dwell any further on Stella. “Mr. Martino sir,” said Yani, shouting from the storage room, “there’s a delivery of carpets, chairs and a new register that needs your signature.” Martino waddled over and was greeted with horse spit showering his freshly washed hair. His new wares were scattered all over the back alley and the delivery men, Mr. Cicogna and his three sons, were loading ever more goods onto the dirt.

“Now wait just one moment—” said Martino, a fresh stream of spittle stopping his speech. Not one moment’s rest being a businessman, thought Martino, wiping his face and trying half-heartedly to get the Cicogna sons to handle his carpets more gently. All of these new fixtures and no respect paid to them…Martino would have a word with the elder Cicogna at the next All Saints festival in February.

Yani wrote two copies of a receipt - one for Martino and one for Cicogna - and started hauling the goods into the Emporium.

“This one is on credit, eh? Comes out to 20,000 Lire,” said Cicogna, rubbing his horse’s mane and looking Martino up and down.

“Precisely, I’m sending Yani to the bank later today to withdraw the cash. You will receive payment in full within thirty days,” said Martino diplomatically. Thank his holiness for net 30 payment terms, so pioneered by his Venetian merchant brothers up North.

Cicogna grumbled in assent and ripped his receipt from Yani’s hand. He looked down and scanned the paper with feigned scrutiny.

“And I see you’ve already included the tax owed to the Messateria. Great.”

“As you know, I have the utmost respect for the tax authorities and businessmen who keep their books in good order,” said Martino severely as Yani rolled his eyes. “As they say, ‘There’s more to the making of a good businessman than to the making of a Doctor of Laws.’”

Mr. Martino grabbed Yani’s wrist as the latter was heading back into the shop. “Yani, be sure to withdraw 30,000 Lire from my account today. No more, no less.”

Martino went back to double checking his inventory list from the night before ("Damn it, we forgot the sugar for the cleaning solution”). His mind was replaying Stella’s words, his conversation with Boot and the feeling of heartburn that plagued him recently. He suddenly felt boxed in, like he willingly trapped himself into an opaque cage just to feel seen. The world outside his little shop was teeming with art and new ideas like geometry and perspective - but in his shop, time stood still. He worshiped the Romans and felt close to them, even though they were a thousand years away. He desperately wanted to be memorialized himself on a piece of silver, forever in someone’s pocket.

He wanted to be useful.

But he was no Sandro Botticelli or Cosimo de’ Medici. He wasn’t even a second rate architect like Brunelleschi. He was Mr. Massimo Martino, an amateur coin collector that couldn’t accept the futility of it all.

“Sir?” Yani was tapping on Martino’s arm and tugging him back into the main shop. “There’s a familiar woman who wants to talk to you.”

Mr. Martino stumbled out of his reverie and came face to face with Alessandra. His Alessandra. She was standing there timidly holding a basket on one arm and wearing an apron, smears of some nondescript liquid painted like embroidery. She really was beautiful with her deep chestnut hair and light eyes, always laughing despite her hard working conditions. She kept The Sullied Goat functioning even though no one seemed to notice.

“Alessandra, so lovely to see you here. Lovely…apron?” Mr. Martino could feel blood rushing to his face and his heart was pounding. Lovely apron? Really? It looks like it’s smeared with cow dung.

Memories came rushing into his mind. Alessandra was married to Mr. Vittolo, a cobbler, but they stopped being in love about fifteen years ago since Mr. Vittolo was cheating on her with Arabella, a model for the local artists. Alessandra and Martino became each other’s source of comfort, and they bonded over their shared love of rosemary bread and history in his storage room. His attic was once a cozy hideaway but he let the rats overrule when Alessandra said their friendship could not continue. He could still remember her words clearly, as if a ghost were whispering them in his ears. “We can’t continue like this. I’m married and even though Vittolo is vile, he’s my husband. I’m happiest with you but our meetings are cast in a dark shade.”

That was five years ago.

Mr. Martino and Alessandra still crossed paths frequently (Sansepolcro was the size of a shoebox), but their eyes would lock only briefly, saying nothing but regret and longing. Martino could still feel Alessandra’s hands in his, their fingers tracing the m-shaped lines on their palms. Her lips always tasted like licorice mixed with cherry. After Alessandra faded away, Martino gave up hope of ever finding another woman to love or be loved by. So he buried himself underneath his coins and succumbed to them.

“Thank you,” said Alessandra, looking anywhere but directly at Martino. “Your shop has grown a lot since I last was in here.”

They both fell silent, remembering the last time she was inside the Emporium.

“I appreciate the compliment. What can I help you with today?”

Mr. Martino moved himself behind his desk to keep some separation between himself and the lady. He could feel an invisible hand pushing him ever closer to Alessandra, and he wanted to save himself the anguish.

“Well I’m not sure if you know, but my son, Sandro, is turning twelve this year. He’s taken up an interest in coin collecting, and I wanted to get him something special for his birthday. And I remember your collection being…one of a kind.”

Mr. Martino’s pulse was trotting now.

“Does Sandro happen to be interested in coins of the Roman variety?”

“He’s too young to be picky just yet - so anything that looks old and is remotely shiny will do.”

They examined the Tetrarchy coins together (that wonderful quartet of Diocletian, Maximian, Constantius I and Galerius), and Mr. Martino settled into his element. He wouldn’t let Alessandra throw him off, not when he was explaining his first love, his first passion.

“And then Diocletian commissioned a massive bath complex, which bears his name, and an immense trove of coins with his face on them were found underneath the hypocaust. No clue how they arrived there.”

Alessandra was studying the coins under the candlelight, the glow casting her wrinkles and sagging lips into high relief. Time hadn’t been kind to his Alessandra either.

“I’ll take them all,” she said without life. “No matter the cost.”

“Well that’ll be 25,000 Lire for all the Diocletian coins we have. Are you sure that’s alright? If you don’t have the Lire now, you can always purchase on credit or exchange another good.”

Mr. Martino spread his arms wide and added with a touch of histrionics - “I’ll take any wheat you have or imported jasmine beads, a pound of rice or an amphora of mulled wine as partial payment.”

Alessandra reached her hand across the counter and laid a firm grasp on his forearm.

“You always were the best businessman I ever knew. Let’s call it 15,000 Lire now and 10,000 Lire I can deliver later. Perhaps tonight?”

The place where Alessandra had placed her hand was boiling. Martino felt like he had just swallowed a pound of sugared stag, which he was deathly allergic to.

“S-sure. Are you sure? Because I’m sure. I mean I’m sure I’ll be here later tonight. Yani and I have to finish up the books, but we’re usually finished by 7. I mean 6:30 because he’s become such an efficient boy now—” Alessandra placed her other hand on Mr. Martino’s mouth.

“I’ll be here at 7:30 - and I’ll bring some rosemary bread.”

Martino exhaled the million questions that were racing around in his head. All of his answers would arrive at 7:30, along with the rest of his heart.

“Perfect, I’ll be awaiting you then.”

They beamed together, puzzled and a little scared but something had changed in the small minutes that had passed. It wasn’t until a few hours later that Yani informed Martino that Mr. Vittolo had died a few days earlier from a horsing accident on the way from Sansepolcro to Milan.

“That poor bastard,” Martino shook his head. “Here, buy some more flowers from Lucretia and deliver them to Alessandra. She must’ve been in shock.”

The doorbell peeled as Yani left and again a mere five minutes later. I can’t get a break today! thought Martino, absolutely exasperated at this sudden rush of commerce. His cousin’s words came back to him: “Businessmen operate on land and sea, in peace and war, during boom and recession, in health and plague.”

Looking up from his books, Martino suddenly heard panting and saw a man doubled over, his hands on his knees.

“Is that you, Mr. Giovanni?”

“Yes,” he sputtered, trying to catch his breath. He was making wild hand gestures towards the window. “Need you, come outside, now.” Then he ran back outside before the bell had time to sing its full tinkle.

Now that’s strange behavior for the local mathematics teacher, thought Martino. But he could hear a small commotion outside and decided to investigate.

The sunlight burned his eyes, and it took a few seconds for them to adjust to the brilliance of a Tuscan afternoon. The air was filled with a woody cypress scent and a gentle breeze. The browned buildings all around him were suntanning and speckled with a terracotta burn. Bell towers and church spires greeted his eyes as he looked toward the horizon.

“Down here!” shouted Mr. Giovanni, bringing Mr. Martino back down to earth.

On the street in front of him, a small scene was developing. At the center of it was Mrs. Giovanni, who was sporting an enormous belly and a pastry in her right hand. Her puppy, Chircomo, was dancing circles around her writhing body.

“She’s in labor!” said Mr. Giovanni, trying to fend off Lucretia’s five children who were prodding and sniffing Mrs. Giovanni’s swollen belly. “I was at the school when one of Lucretia’s kids burst into my classroom. The baby isn’t due for another month,” he cried out.

At that moment, Yani rounded the corner, whistling with his hands in his back pocket.

“Oye Yani! Call for a carriage!” Mr. Martino yelled, throwing a 10-piece Lire down the street. Yani turned on his heel and went back the way he came at a slow jog.

Mr. Martino knelt beside the trembling Mrs. Giovanni. Her black hair was mussed around her face, and her eyes were wild with fear. An oval of blood was starting to spread near the bottom of her lilac robes. Rumors were circulating that her sister, Mrs. Marguerite Fresca, had died a few months earlier in childbirth.

“Listen to me Mrs. Giovanni, you will deliver this baby by the grace of God and you will both survive. I’ve seen the way you stride with purpose, even when you’re so far pregnant. Nothing can stop you, not even a child that’s anxious to get out and see the world.”

Mrs. Giovanni groaned, her legs continually crossing and uncrossing again.

“Here, sip some of this.” Mr. Martino took out his flask and poured a measure of wine into Mrs. Giovanni’s mouth before giving the rest to Mr. Giovanni, who was vomiting by the street drain. At that moment, a horse-drawn carriage came roaring around the corner and stopped in front of Martino.

Yani jumped off and silently lifted Mrs. Giovanni into the back, not even minding the blood that was soaking his arms and shirt. Martino quickly ran into the Emporium and grabbed his last Augustus denarius. Returning to Mrs. Giovanni, he pressed the coin into her hand and whispered, “Now you will be okay, I promise.”

“Don’t forget to account for that denarius in our books tonight, consider it a donation,” said Mr. Martino to Yani as they headed back into the shop. They changed clothes (Martino always kept a spare outfit at all times for occasions such as this) and collapsed on the floor.

“I think this has been the most eventful day since our Cathedral remodeling was completed,” huffed Yani, rubbing his toes.

“Those new spires really are something,” said Martino, utterly exhausted. He was getting too old for the life of a businessman, too worn down to withstand the highs and lows of Italian commerce. Was he a merchant or just a retiree? It would be easy to pass the shop onto Yani and live out his days in the Sansepolcro countryside, sheep and lowing cattle replacing schoolteacher’s wives in labor.

Just then, the bell rang again.

“We’re closed for the day, please come back lat—” began Mr. Martino, lumbering to his feet. Something must be in the air today, nobody likes ancient coins this much.

He was stopped dead in his tracks by a figure so stately and regal that words failed him.

Prince Lorenzo, the middle son of the Medici dynasty, was gracing their carpet. He was wearing an embroidered cape and royal blue leather gloves. His face was a smooth white - not a blemish in sight - and his eyes were a cold hazel.

“Prince Lorenzo! My goodness, welcome to Mr. Martino’s Emporium. My apprentice Yani and I are at your service.”

Yani’s mouth was agape.

A soft cooing broke the silence as Prince Lorenzo surveyed the sweating duo.

“Don’t mind the pigeon,” began Prince Lorenzo, stepping forward. “It’s my dear pet, Picci. I bring him with me everywhere.”

He spoke in exaggerated intonations that were uneven and unsettling. Picci the pigeon gave Martino and Yani a judgmental stare.

“I think pigeons are wonderful—” began Yani, but Mr. Martino cut him off.

“We’re humbled by your presence my sire. We’ve heard tales of your wonderful cavalry training and battle experience. We are truly lucky to have a Prince like you defending the humble interests of Sansepolcro.”

Mr. Martino made a slight bow for dramatic effect.

“Pray tell, what’s your most expensive coin?” inquired Prince Lorenzo, walking about the small shop as if he owned it.

“That would be our 250 B.C denarius depicting the She-wolf and Romulus and Remus, the brother founders of Rome. Solid silver and one of the oldest, most intact you’ll find.”

Mr. Martino offered the coin to the Prince, the suckling scene warming the Prince’s cold face by a few degrees.

“It’s wonderful,” murmured the Prince, rubbing it between his gloved hands. “I’ve had a fascination with coins ever since I was a boy, but all the sellers between Sicily and the Dolomites sold nothing but fakes. I am a connoisseur, you know, so I’m able to discern the false from the true.” He then turned his gaze to Mr. Martino. “And this is no fake.”

“I have connections with a very trustworthy coin excavator, he goes between here and Rome once a week for fresh inventory.”

The Prince nodded in approval. “As did I. But lately I discovered my dealer was taking bribes from other coin merchants to peddle their wares to me. Fools, the lot of them, thinking they could outwit me.”

“I’m a Prince,” he added for emphasis.

“That coin in particular is normally 50,000 Lire but as a symbol of our goodwill, please take it at no charge,” said Martino, not wanting to negotiate with this lion.

“Nonsense,” said the Prince, rummaging in his pocket. He hurled something towards Yani and slipped the She-wolf into one of his many pockets. “That’ll be a gain on this transaction for you, Mr. Martino. I’ll remember you. Now if you’ll excuse me, I need to get back to my princely duties.”

He wheeled his leather heels around and left the shop, Picci the Pigeon not taking his beady eyes off Mr. Martino until they disappeared.

“He gave us a diamond sir! A real diamond. Look -”

Yani stepped into chink of sunlight that was peeking through the curtains. It was a small circle, the size of a cluster of peas, but it was a kaleidoscope of truth and beauty. Mr. Martino could see himself reflected in that mirror, see his receding hairline and doughy nose. But his heart was swelling.

“That gem is worth 80,000 Lire, my son,” he said. “What magnanimity.”

Mr. Martino walked trance-like to the front door and flipped the sign from “aprire” to “chiuso.” He realized something in the split second between the sign turning from one state (open) to another state (closed). It was his hand that determined his hours and where he spent the remainder of his days. He wasn’t going to wait for women that toyed with him or a conscience that only reminded him of his mortality. He was going to the one place where he was truly alive: the ruins of Ancient Rome.

“Yani, fetch me three pieces of paper please. I have a few notes to send off tonight before we do the books for the day.”

Letter One

Dear Alessandra, I’m devastated to hear about the passing of your late husband, Mr. Vittolo. I’m sure you are in the throes of grief right now, and I don’t want to upset this natural process. Please accept these flowers from me and my assistant. We have shop matters to attend to tonight so I will be unavailable. Yani will come around on Friday to collect the remainder of your payment due. Take care -

M

Letter Two

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Giovanni, May fortune smile upon your womb! You are both in my thoughts and prayers, and I wish for nothing but the cry of a new baby in this world tonight. Please send word of the good tidings, as they will surely come. Take care - M

Letter Three

Boot, If you’re still in town, meet me at the corner of Dittalini and Riggolo at 10 pm. I hear Reni is performing tonight. M

Mr. Martino and Yani sat down at the desk and opened their leather-bound book between them. It was their daily ritual to “close the books” every night with all activity for the day. Most days there was nothing to do - an empty page - but today, January 2, 1493 was exceptional.

“So where do we begin?” asked Yani, grinning. He loved doing the books and found no greater pleasure than when debits and credits equaled in their neat, commanding columns.

Mr. Martino chuckled and rubbed his belly. He pulled a bottle of merlot out from under the desk and popped the cork.

“Let’s start with Stella’s sale.” He looked at Yani fondly and was confident the boy would be an excellent successor to the Emporium.

What my cousin says is true, I suppose, thought Mr. Martino.

‘Regular accounting leads to lasting friendship.’

Glossary

-

Solidus - pure gold coinage introduced by Constantine the Great in 312 A.D.

-

Denarius - silver coin introduced in the Second Punic War (211 B.C.); means “containing ten” in Latin

-

Sestertius - originally a small silver coin in the Roman republic; later rebranded to a large brass coin during the reign of Augustus

-

Antoninianus - bronze coin introduced by the emperor Caracalla in 215 A.D.

-

Sansepolcro - small medieval town in the province of Arezza; birthplace of Luca Pacioli and Piero Della Francesca (artist)

-

Julio-Claudian Era - the first dynasty of the Roman Empire that ruled from 27 B.C. to 68 A.D.; includes the Emperors Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero

-

Doge - chief leader (“duke”) of the republic of Venice; title was used from 697 - 1802 A.D.

-

Messataria - tax authorities in Renaissance Italy

-

Sandro Botticelli - Italian Renaissance painter from Florence (1445 - 1510 A.D.); famous for the “Birth of Venus” painting

-

Cosimo de’ Medici - preeminent Florentine banker, politician and patron of the arts; had great influence over Florentine politics in the 15th century

-

Filippo Brunelleschi - pioneer in Renaissance architecture; designed the dome of the Florence Cathedral and was also a sculptor, master goldsmith and painter (he is credited with inventing linear perspective)

-

Tetrarchy - system of ruling the Roman Empire devised by Diocletian in 293 A.D. In this system, there would be two prevailing rulers (for the eastern and western halves of the Empire) and their two successors/junior assistants

-

Hypocaust - an underground system of central heating used in Ancient Roman bath complexes; a furnace would be kept and the ensuing hot air would filter through tiles and concrete into the rooms above