Still Life with a broken Glass, Willem Claesz. Heda, 1642

I recently had the chance to lead the book club for she256, a nonprofit dedicated to advancing women and minority interests in crypto. We kicked off our first meeting with Sacred Economics by Charles Eisenstein, a treatise spanning economics, self-help, monetary policy and spirituality. It was an unusual pick for crypto internet strangers but also so refreshing - I had an incredible time talking about random topics like universal income, commoditization of life, squirrel habits and more. In my opinion, a truly fantastic book is one that makes you question your preconceived notions and changes your perspective from your bedroom. Sacred Economics is going to stay within my mind for a long time, and I hope Charles’ vision of The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible comes true.

To facilitate conversation, I created discussion questions and summary slides for our club members - see below for the complete book club guide to Sacred Economics!

Part I

The Tower of Babel by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Chapter One

What is your definition of a gift? According to that definition, what sort of expectations do you have about giving and receiving?

What are some connotations of the word “sacred,” and what are your thoughts about applying that word to economics and money, two concepts not traditionally thought of as sacred?

Can economics and money actually become sacred?

Chapter Two

Eisenstein often repeats that “we live in a world of abundance” - how does this reconcile with climate change and poverty? Do you agree or disagree with his statement that “the assumption of scarcity is false”?

The first part views humanity as a progression towards Separation - humans from nature, spirit from matter, humans from community/relationships, etc. What are other examples of separation in human life? How did we get there?

What affects have there been on humanity by holding our basic assumption that everything in life is scarce?

Chapter Three

Eisenstein writes that money is basically an illusion or an invisible social agreement between people. What other parts of human life are technically fiction? And how is it possible that these fictions drive human behavior and activity?

Consider this paragraph:

Those reformers who advocate gold coinage (or cryptographic imitations of it, such as bitcoin) as a way to return to the good old days of “real money” are trying to return to something that almost never existed.

What does Eisenstein mean by this? Is Bitcoin/crypto not the final frontier of money we think it has the potential to be?

- As a society, we turn everything into a commodity that can be bought and sold for money. What are the consequences of this line of thinking? Consider the philosophical developments in Ancient Greece that accompanied the invention of money as well.

Chapter Four

What does Eisenstein mean when he writes that “we are relationship.” What does this say about the fundamental nature of humans and our place in the world?

The book asserts that seizure of once free and open lands, roamed by natives or unoccupied, was the original theft. Humans took land that was already existing, began farming on it (improvements to the land) and subsequently bought and sold the land for ownership. What does this say about our current system of rampant private property?

Can you truly “own” nature?

Compare and contrast Henry George’s and Silvio Gesell’s view of property ownership and their solutions to the property problem. (page 80)

Has anyone had any experience with the roaming laws in Europe (i.e. the concept of trespassing doesn’t exist because walkers/campers can use private property)? What did that feel like?

Chapter Five

The basic premise of the chapter is that humans are converting all realms of capital - natural, social, cultural and spiritual - into money. Briefly describe these different types of capital and ways they’re being “strip-mined” for money.

How has the human attention span been affected by the commodification of entertainment?

Compare qualitative and quantitative needs. How has money met or failed to meet those needs? Can money truly solve all of our problems?

What needs have been artificially created by money and the ever-present demand of more and more economic growth?

Chapter Six

How does our current interest-based system work? What is the ultimate lesson from the parable of The Eleventh Round?

Because of the way new money is created, debt is always greater than existing money and (usually) the rate of economic growth. Why was the system created this way? How does this affect the debtors versus the lenders?

What are the downsides and/or upsides to the economic imperative for continual growth? What happens if we stop growing economically?

Compare the current monetary system from the point of view of a wealthy individual from that of a debtor. Does this shed insight on why “in an interest-based system, class conflict is inevitable?”

What’s your initial reaction to the concept of debt repudiation (basically, refusing to repay your creditor)?

Chapter Seven

The concept of “Peak Everything” implies that we’ve exhausted all the commons and positive economic growth is nearing impossible. Do you agree or disagree with this premise? Do you think true economic growth can happen in new industries like crypto?

How does Eisenstein explain and frame the 2008 financial crisis and similar bubble bursts?

How does the imperative of economic growth affect the human psyche? How do you think we’d act or feel if we were in a gift economy and/or hadn’t expended the common capital?

Chapter Eight

Do you think it’s fair to say our current monetary system is mere “ritual and talisman,” and that you can compare indigenous shamanic rituals to Wall Street?

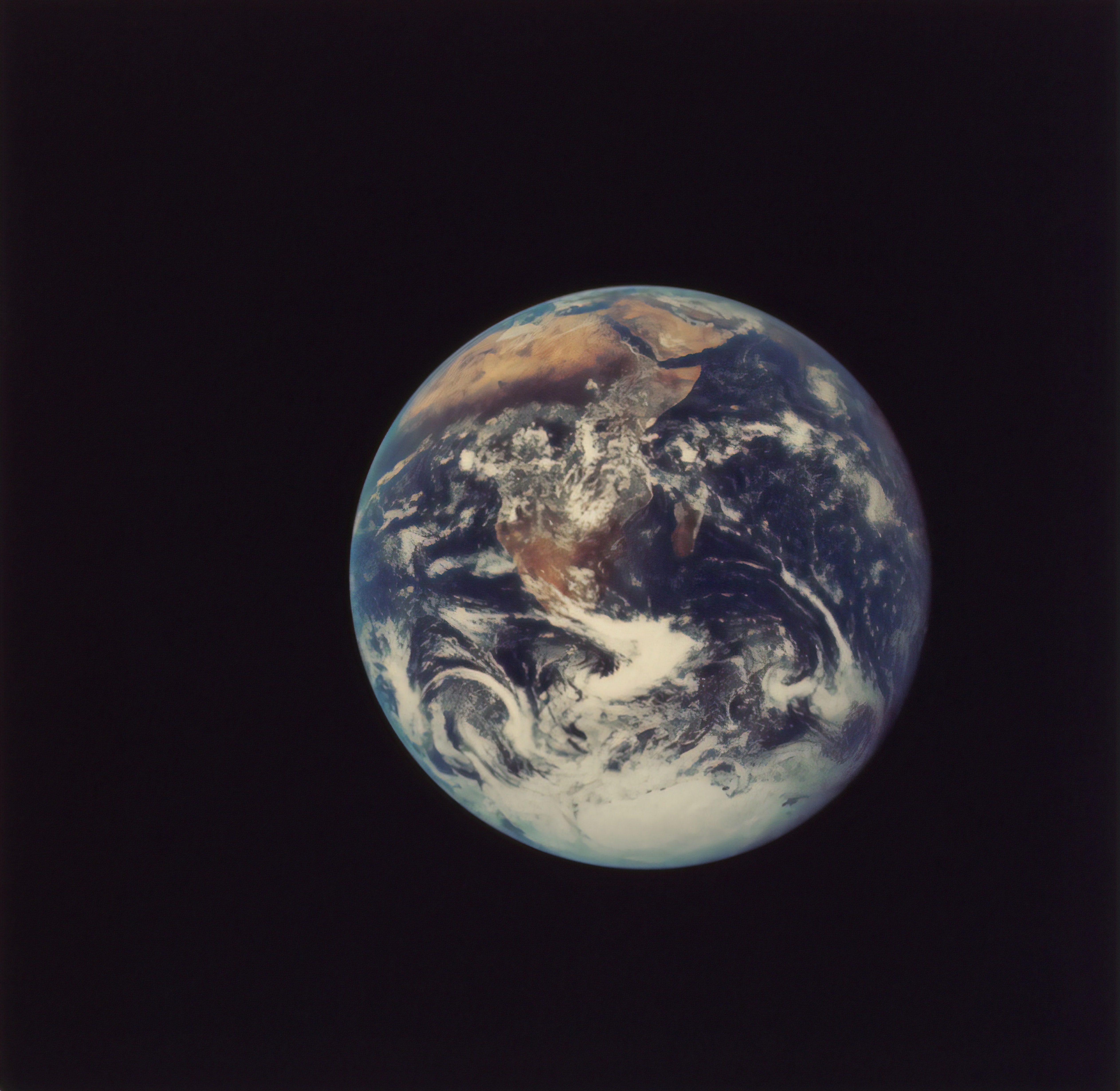

What was the effect of humanity being able to glimpse earth from outer space, the “penultimate step of separation from nature?” What emotions does the image below conjure?

Image courtesy of Nasa.gov

- According to the author, we are entering the age of “more for me is not less for you.” Do you think this idyllic state of a gift economy and usury-free money can actually come to fruition?

Part II

Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash

Chapter Nine

Since money is a story about value and what humans have collectively agreed to use, how different is cryptocurrency to fiat backed by gold? Does cryptocurrency actually provide a new and enhanced value proposition?

What do you think about Eisenstein’s idea of “backing” money with clean air, unpolluted waterways, energy credits, the cultural commons, etc? Can this actually happen or is it idealistic?

Chapter Ten

What are the effects of large corporations internalizing the costs of externalities? What sort of future would this look like (and would those big corporations actually go for this)? (a) Triple bottom line (b) Full-cost accounting

Is financially valuing the ecosystem, which gives us infinite benefits, actually more detrimental in the long term? Will it actually force humans to consider the earth as sacred again?

How does politics come into this? Won’t mega-corporation lobbyists prevent the cap-and-trade systems and direct taxes on pollution from coming into effect?

Chapter Eleven

Eisenstein writes “I envision decentralized, self-organizing, emergent, peer-to-peer, ecologically integrated expressions of political will.” This sounds a lot like the pillars of cryptocurrency, so how could crypto play a role in Sacred Economics? Proof of environment??

How is government (or the perception of government) going to have to change to truly become a “trustee of the commons”?

Can Eisenstein’s vision of transitioning to a currency backed by the commons actually happen? Is this realistic in our lifetimes?

How does this localization of economics and money fit into the trend of a globalized world? People are more mobile than ever and aren’t so tied to local economics.

What would Corporate America (i.e. Walmart, Target, Exxon) think about this?

Does our current taxation system (i.e. taxing income and goods in circulation while letting wealth accumulate untaxed) have it totally backwards?

Chapter Twelve

What are your thoughts on negative interest money, the idea that money gets less valuable over time? What would money become then?

Negative interest effectively imposes a tax on hoarding - what would the economy look like if money was freely circulated without taxation?

How could we implement the ideas of a stamp script currency with today’s technology? (Doesn’t Bitcoin already do this with their halving events?)

How do you think the public would react to a negative interest rate on their debt and/or investments?

What sort of mind shifts come along with a negative interest economy?

“Lowering interest rates below the zero lower bound makes investments possible that have a zero or negative return on capital.” → Based on this theory, what sorts of investments would happen in a negative interest economy that wouldn’t happen today?

Do you agree with the Austrian School of Economics’ claim that “it is human nature to want to consume as much as possible right now?" Are humans really that attached to hedonism and instant gratification?

On a similar note, saving money has been seen as a virtue of self-restraint (which conveniently comes with interest attached). Is this just an excuse for hoarding wealth?

Essentially, negative interest economics promotes a gift and sharing economy akin to our hunter gatherer primitives. Do you think switching to this economy is a good thing? Is it even achievable?

Chapter Thirteen

Do you think humanity is going to peak and crash or is the transition to a de-growth economy going to happen more smoothly?

Why didn’t the hippies succeed in ushering the world into a more sacred economy?

How can the internet enable a sacred economy that depends less on the monetized realm and more on P2P interactions?

How have internet giants like Facebook, Google and Amazon tainted the original spirit behind the internet?

What’s your favorite internet platform that allows for the disintermediation of services?

How do you think people will react to the idea of a shrinking economy?

Chapter Fourteen

For those who are currently employed, what projects would you pursue or how would you use your leisure time if traditional working hours were cut by 20%?

How would you describe the current working culture of developed nations?

How is it that humans have all this time-saving technology yet we work harder than ever in jobs we find draining?

If people had ample leisure time, do you think we’d degenerate and become lazy? Or would we actually use our natural gifts to clean up toxic waste sites, create art, take care of the elderly, etc?

Do you think it is “human nature to desire never to give but only to take?” Are humans fundamentally selfish or giving?

Question from the book: “What would the world be like if people were supported in doing the beautiful things they must struggle against economic necessity to do today?” (a) “What am I here for?” (b) “Must we resign ourselves to a society in which some people must do work that is beneath them, coerced into it by money-based survival pressure?”

Chapter Fifteen

What shift would take place if humans were deeply connected to their communities for the giving of gifts & meeting of needs, instead of depending on far-flung strangers and corporations?

How would crypto play a role in enabling local currencies?

How do developed countries defeat the Catch-22 paradox that faces the adoption of local currencies?

What are everyone’s thoughts on time-banking? Should we create a beta time bank for the she256 community?

Unlike any other possession, as long as we are alive, our time is inseparable from our selves. Our choice of how to spend time is our choice of how to live. And no matter how wealthy one is in terms of money, it is impossible to buy more time.

Is cryptocurrency (in its current form) really a good thing if its default state is distrust?

How do DAOs exemplify sacred economics?

Chapter Sixteen

Aren’t social tokens a way to measure “the esteem of peers, based on the quality and quantity of previous contributions”?

What are the pros and cons of quantifying the qualitative, of reducing the infinite to a basic number?

I’m constantly amazed by the internet and how much of its infrastructure, interactions and products are free - what if the rest of the world had this P2P mindset?

Has anyone tried GIFTegrity, gift circles or similar experiments in small-scale gift economies?

How are gift economies going to scale in a global world? Or will the world naturally become more localized (and is that a good thing)?

What role will DAOs play in a sacred economy? How will they revolutionize the way we work?

Chapter Seventeen

Out of the 8 tenets of Sacred Economics, which one do you find the most fascinating?

Are these Sacred Economics tenets feasible or just an interesting thought experiment?

Part III

Photo by Jeremy Bishop on Unsplash

Chapter Eighteen

How do you think our culture of Venmo requests and nickel & diming affects forming relationships with other people?

Have you ever caught yourself refusing a gift or downplaying a compliment - why do you think that was?

Is dependence on society and favors from other people (i.e. a gift economy) a good thing? Or do you think humans naturally desire to be independent?

What is the most memorable or shocking gift you have ever witnessed?

Chapter Nineteen

Would you ever voluntarily adopt income topping (i.e. pledging to never earn more than X amount of money per year)? Do you think this principle is a net positive for society?

Have you ever questioned your motives when you performed an apparently authentic act?

Do you agree with Eisenstein when he says there’s no point in accumulating wealth since we’re going to die anyway? Consider how this passage affects you:

We are all going to die anyway, and no matter how long you live, the moment will come when you look back upon your years and they seem short, a flash of lightning in the dark of night, and you realize that the purpose of life is not after all to survive in maximum security and comfort, but that we are here to give, to create that which is beautiful to us.

- Do you think the default state of humanity is misery and competition or free-flowing gifts & beauty?

Chapter Twenty

Do you agree with Eisenstein’s viewpoint that ethical investing and socially conscious investing are basically a scam?

What will it take to persuade the millionaires & billionaires of the world to start sacred investing and investing in ventures with zero or negative returns?

Are humans really brimming with pent-up gratitude like Eisenstein implies? Or will giving your wealth away lead to people taking advantage of your kindness? (which again begs the question, what is the default morality of humanity?)

Would you quit your job, which probably contributes to the “earth-devouring machine,” to live in right livelihood (i.e. reskilling courses, training holistic healers, teaching permaculture)?

Chapter Twenty-One

If you were a great artist or musician, would you be comfortable giving away your work for free and only accepting ad hoc donations?

For people that are already doing this today (i.e. content creators), does this model work?

Charles writes about gift culture but also receives fees for his speaking engagements - do you think this fits in with Sacred Economics?

Have you ever encountered a business that used gift economics to pay (i.e. presenting the costs and then another box to enter a gift amount)?

Do you think traditional businesses like manufacturing will adopt this?

How do these “gift payments” work on a global scale?

Have you ever been to a pay-what-you-want restaurant?

Chapter Twenty-Two

Do you think communities that don’t rely on the actual meeting of needs are still useful & impactful (i.e. she256)?

Do you agree with Charles when he says “The things we need the most are the things we have become most afraid of, such as adventure, intimacy, and authentic communication? → do you feel like you are missing these things in your life?

Chapter Twenty-Three

Do you think everyone contains the mastery & genius of a Michelangelo or Picasso inside them? Has our “exuberant expressions of our gifts” been suppressed by society that much?

Do you think Eisenstein’s comparison of Soviet dispensaries to Walmart superstores is fair? Or have we debased & commoditized our goods that much?

What does a sacred object mean to you?

Wrap Up Questions

Do you think implementing Sacred Economics is feasible and achievable by current society?

Can you offer any alternative explanations for our current calamities (i.e. COVID, natural disasters, financial crises) besides money/debt creation and the growth imperative?

Describe the best case & worst case scenario for Sacred Economics playing out in our world.

Out of 10, how would you rate the book and why?

Did Sacred Economics change your viewpoint of the world? What principles (if any) will you bring forward in your life?

Ultimately, then, Sacred Economics is part of the healing of the spirit/matter divide, the human/nature divide, and the art/work divide that has increasingly defined our civilization for thousands of years. 🌸